Julie Nixon Eisenhower

Julie Nixon Eisenhower | |

|---|---|

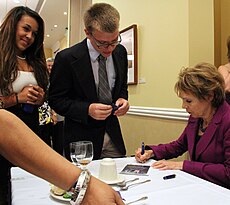

Nixon Eisenhower in 2010 | |

| Born | Julie Nixon July 5, 1948 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Education | Smith College |

| Occupation | Author |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3, including Jennie |

| Parents | |

Julie Nixon Eisenhower (born July 5, 1948) is an American author who is the younger daughter of former U.S. president Richard Nixon and his wife, Pat Nixon. Her husband, David, is the grandson of former U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower and his wife, Mamie Eisenhower.

Born in Washington, D.C. in 1948, while her father was a Congressman, Julie and her older sister, Tricia Nixon Cox, grew up in the public eye. Her father was elected U.S. Senator from California when she was two and Vice President of the United States when she was four. Her 1968 marriage to David Eisenhower was seen as a union between two of the most prominent political families in the United States.

Throughout the Nixon administration (1969 to 1974), Julie worked as the assistant managing editor of The Saturday Evening Post while holding the unofficial title of "First Daughter". She was widely noted as one of her father's most vocal and active defenders and was named one of the "Ten Most Admired Women in America" for four years of the 1970s by readers of Good Housekeeping magazine. After her father resigned from the presidency in 1974, she wrote a biography of her mother, the New York Times best-seller Pat Nixon: The Untold Story. She continues to engage in works that support her parents' legacies and is on the board of directors of the Richard Nixon Foundation.

She is the mother of two daughters, Jennie Eisenhower and Melanie Catherine Eisenhower, and a son, Alex Eisenhower.

Early life and education

[edit]

Julie Nixon was born at Columbia Hospital for Women in Washington, D.C., while her father, Richard Nixon, was a Congressman, but much of her childhood coincided with her father's term as Dwight Eisenhower's vice-president (1953–1961). She recalled her father as being romantic, while her mother was "practical and down to earth".[1] Her mother tried to "seal" her and her sister from much of her father's political career.[2] At his second inauguration, President Eisenhower suggested to eight-year-old Julie as their photograph was being taken, to hide a black eye (which she had acquired in a sledding accident) by turning her head. She turned her head towards David, which made it appear that he had been staring directly at her.[3] Her grandmother Hannah Nixon would come to watch her and her sister whenever her parents traveled.[4] As a child, one of her favorite pets was a cocker spaniel named Checkers, who figured prominently in one of her father's most famous speeches, given during his 1952 campaign for Vice President of the United States.

While her father was vice president, she attended the private Sidwell Friends School in Washington, D.C., along with her sister Tricia. After her father lost the presidential election of 1960 to John F. Kennedy, Julie felt "battered" by the results and felt that the votes had "been stolen".[1]

After her father lost his presidential bid in 1960 the family returned to California, where her father ran unsuccessfully for governor in 1962. The Nixons moved to New York City after the gubernatorial race, and Julie attended Smith College after her graduation from the Chapin School.[5] She received a master's degree in education from Catholic University of America in 1971. When she was at Smith, David Eisenhower, the grandson of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, attended Amherst College nearby. Julie and David were both invited to address the Hadley Republican Women's Club. The club learned that the two were only seven miles apart, and invited them to be featured speakers.[6] They discussed the invitations and both chose to decline, but would come in contact again when David visited Julie with his roommate from Amherst and took her and a friend out for ice cream. David reflected: "I was broke, my roommate forgot his wallet. The girls paid."[7]

Marriage

[edit]

She began to date David Eisenhower in the fall of 1966 when they were freshmen at Smith College and Amherst College, respectively. They became engaged a year later. [8] Both Julie and David have said that Mamie Eisenhower played a major part in their relationship.[9][10] In 1966 during the funeral for Raymond Pitcairn, a friend of the Nixons, Julie mentioned to Mamie that she would be attending Smith College. Mamie told her of David's plans to go to Amherst College, and soon started trying to get David to call on her.[11]

In 1966, Julie Nixon was presented as a debutante to high society at the International Debutante Ball at Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City. David Eisenhower was her civilian escort at the International Debutante Ball.[12]

Julie and David married on December 22, 1968, after her father was elected president in the 1968 presidential election, but before he took office. The couple decided they did not want the publicity of a White House wedding.[13] The Reverend Norman Vincent Peale officiated in the non-denominational rite at the Marble Collegiate Church in New York City.

The couple left Massachusetts in 1970 when their classes there were canceled after the Kent State shootings. After her father resigned from office, the two lived in California near Julie's parents and later in the suburbs of Philadelphia.[14] The Eisenhowers have three children: actress Jennie Elizabeth (born August 15, 1978), [15] Alexander Richard (b. 1980), and Melanie Catherine Eisenhower (b. 1984), a Child Life Specialist in the oncology department at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.[16]

First daughter

[edit]

During the United States presidential election of 1968, when her father was the Republican nominee, Julie began to feel that she was not active enough in her father's campaign and worried over what she believed was Hubert Humphrey's popularity at Smith College, which she was attending at the time.[17] She took an active role in his campaign, and shook hands for hours while greeting people. Despite not liking the publicity and hating to answer "personal questions", she did anything she could to help her father.[18]

While her father served as President (1969–1974), Julie became active at the White House as a spokesperson for children's issues, the environment, and the elderly. She gave tours to disabled children, filled in for her mother at events, and took an active interest in foreign policy. She and Tricia were placed in charge of Caroline Kennedy and John F. Kennedy, Jr., when they visited the White House in 1971. The sisters took the young Kennedys on a tour of their former residence, which included going to their old bedrooms and to the Oval Office.[19]

In 1971, when David was assigned to the Mayport, Florida-based USS Albany, they moved to the Jacksonville beach community of Atlantic Beach, Florida. She had been hired to teach third grade at Atlantic Beach Elementary School beginning that fall, but she had to quit when she broke her toe just before classes were to start. The Eisenhowers continued to live in Atlantic Beach until 1973, even hosting the President and the First Lady at their beachfront garage apartment on Beach Avenue.[20]

From 1973 to 1975, she served as Assistant Managing Editor of the Saturday Evening Post and helped establish a book division for Curtis Publishing Co., its parent corporation. It was during this time that Julie wrote the book Eye On Nixon, full of photographs of her father's first administration.

After the news of the Watergate break-in and suspicions that it might reach as high as the Oval Office began to mount, Julie took on the press at home and abroad. Journalist Nora Ephron wrote, "In the months since the Watergate hearings began, she [Julie] has become her father's... First Lady in practice if not in fact."[21]

Taking on the "role of trying to explain her father to the world",[22] Julie's public defense of her father began at Walt Disney World on May 2, 1973. She gave a total of 138 interviews across the country. On July 4, 1973, she told two reporters that her father had considered resigning over Watergate, but that the family had talked him out of it.[21] On May 7, 1974, Julie and David met with the press in the East Garden of the White House. She announced that the President planned "... to take this constitutionally down to the wire."[21] Just before noon on August 9, 1974, Julie stood behind her father while he gave his goodbye speech to the White House staff. She later said it was the hardest moment for him.[21]

Life after the White House

[edit]

Julie and David settled in Berwyn, Pennsylvania, where she wrote several books, including Pat Nixon: The Untold Story and Going Home to Glory; A Memoir of Life with Dwight D. Eisenhower, written with her husband David Eisenhower. She has an extensive record of community service and a special interest in at-risk youth. For over twenty years she served on the board of directors for Jobs for America's Graduates, a national organization that helps young people graduate from high school and transition into a first job. She was named a Distinguished Daughter of Pennsylvania for her civic contributions.[23] She is active with the Richard Nixon Foundation, sitting on its board. From 2002 to 2006 she was Chair of the President's Commission on White House Fellowships, a program fostering leadership in the nation's most exceptional young adults.[24]

Along with her sister and father, she was with her mother when she died of lung cancer on June 22, 1993.[25] Four days later on June 26, 1993, she attended her mother's funeral service on the grounds of the Richard Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California. Ten months later, she was by her father's bedside with her sister when he died.[26] Julie attended the funeral on April 27, 1994.[27] Her father's death left her and her sister with his diary entries, binders and tapes among other things.[28]

She has expressed distaste in a few adaptations of presidencies, and labeled them as giving young viewers a "twisted sense of history".[29] This extended to Oliver Stone's film Nixon, an adaptation of her father's presidency.[30][31] Walt Disney's daughter, Diane Disney Miller, wrote a letter to Julie and her sister saying that Stone had "committed a grave disservice to your family, to the Presidency, and to American history".[32]

On April 14, 1999, the U.S. Department of Defense moved to prevent her from making an appearance to testify during a legal battle over whether the federal government would pay her father's estate millions designated for the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in compensation for papers and tapes seized when he resigned.[33]

In 2001, she expressed interest in exhuming the body of Checkers, a dog attributed to her father's career when he campaigned for vice president that died in 1964. Her desire was to move the remains to the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.[34]

She and her sister got into a legal battle over an estimated "as-high-as" $19 million, left by Bebe Rebozo for the Richard Nixon Library and Birthplace Foundation. As opposed to Tricia's wish for the money to be controlled by a group affiliated with their family, Julie wanted it to be controlled by the library's board.[35] On the relationship strain the two were experiencing during the dispute, Julie said "I think it is very sad"[36] and stated, "It's very heartbreaking because I love my sister very much".[37] Ultimately, the lawsuit was settled to the satisfaction of both sides.[38]

One of Eisenhower's fondest wishes was for the Nixon Library to join the National Archives-administered system of Presidential Libraries:

It's not right, struggling for the money. My father should be in the system. As long as he's on the outside, historians will continue to look at him, I feel, in a more negative light. There is always going to be negativity, but he has to be part of the continuum of presidents.[36]

Due in large part to Julie Eisenhower's advocacy, the Nixon Library became part of the National Archives and Records Administration system in July 2007.[39]

In spite of her family's history of supporting Republicans, Julie donated $2,300 to Barack Obama in the 2008 Democratic primary race against Hillary Clinton.[40][41] She supported Mitt Romney in 2012, the Republican nominee against President Obama, and Donald Trump in 2016, 2020 and 2024.[42]

On March 16, 2012, she and her sister arrived in Yorba Linda, California, to celebrate what would have been their mother's 100th birthday.[43] On November 23, 2013, Eisenhower and her husband opened a holiday exhibit for the Nixon Library, which remained there until January 5, 2014.[44]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Julie Nixon Eisenhower Remembers Her Mother and Former First Lady Pat on the Centennial of Her Birth". April 8, 2012. Archived from the original on November 26, 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Pat Nixon A&E Biography

- ^ Frank, pp. 286-287.

- ^ Frank, p. 76.

- ^ "The Day - Google News Archive Search".

- ^ Wead, p. 261.

- ^ Gibbs, p. 253.

- ^ Berger, Brooke (February 15, 2013). "Eisenhower and Nixon: Secrets of an Unlikely Pair". U.S. News.

- ^ "Gloria Greer with Julie Nixon Eisenhower". February 2, 2002.

- ^ "An Evening with David and Julie Eisenhower". January 26, 2012.

- ^ Eisenhower, p. 210.

- ^ Yazigi, Monique (January 1997). "The Debutante Returns, With Pearls and Plans". The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ Eisenhower, Julie (1986). Pat Nixon the Untold Story. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781416576051.

- ^ Frank, p 344.

- ^ Julie Nixon Eisenhower at IMDb

- ^ "Melanie Eisenhower". Richard Nixon Foundation. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- ^ "My College Diary by Julie Nixon Eisenhower".

- ^ "Julie Nixon 'Will Do Anything' To Help Her Father's Campaign". The Norwalk Hour. March 4, 1968.

- ^ Leigh, Wendy (1999). Prince Charming: The John F. Kennedy, Jr. Story. Sourcebooks. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-0451178381.

- ^ Kerr, Jessie-Lynne (June 26, 2002). "Nixon daughter fondly recalls First Coast". The Florida Times-Union.

- ^ a b c d David, Lester and Thomas Y. Crowell. The Lonely Lady of San Clemente. New York, 1978. p. 172-174.

- ^ Marton, p. 193.

- ^ "Records of the Distinguished Daughters of Pennsylvania". PA State Archives.

- ^ "Commissioner Service Dates".

- ^ "EX-FIRST LADY PAT NIXON DIES OF LUNG CANCER AT 81". The Buffalo News. June 22, 1993. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014.

- ^ "Nixon Motto: 'The Worst Thing A Politician Can Be Is Dull'". Chicago Tribune. April 24, 1994.

- ^ Warshaw, p. 242.

- ^ McGraw, Seamus (May 18, 1994). "NIXON DIARIES WILL STAY A FAMILY SECRET". The Record. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014.

- ^ "Movies Twist History, Julie Nixon Argues". Chicago Tribune. November 21, 1996.

- ^ Wills, Garry (January 10, 1996). "'Nixon' Outrage Proves Truth Hurts". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014.

- ^ "Nixon (1995)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ "Nixon's Family, Disney's Daughter Attack Stone's Film". Associated Press. December 20, 1995.

- ^ Pasco, Jean O.; Weinstein, Henry (April 15, 1999). "U.S. Moves to Block Testimony in Trial". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 25, 2013.

- ^ "Julie Nixon's Pet Project: Relocating Checkers". Los Angeles Times. June 23, 2001.

- ^ Greene, Bob (March 26, 2002). "What Nixon's best friend couldn't buy". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ a b Kasindorf, Martin (April 29, 2002). "Family feud stains efforts to burnish Nixon's legacy". USA Today.

- ^ Pfeifer, Stuart; Goldman, John J.; Willon, Phil (March 2, 2002). "Views Emerge in Rift Between Nixon Sisters". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Sterngold, James (August 9, 2002). "Nixon's daughters end rift over gift". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Library History". nixonlibrary.gov. National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on November 11, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2016.

- ^ "Nixon’s Daughter Talks Watergate, Electing Woman To White House During Pittsburgh Visit", CBS Pittsburgh, September 13, 2014.

- ^ AP. "Nixon's daughter gives to Obama", ABC News, April 22, 2008. Accessed April 22, 2008.

- ^ "Search Results: Eisenhower, Julie". OpenSecrets.

- ^ Movroydis, Jonathan (March 16, 2002). "Julie and Tricia Nixon Celebrate First Lady's 100th Birthday". Richard Nixon Foundation. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ "'Trains, Trees and Traditions' at Nixon Library". Orange County Register. November 23, 2013.

- General sources

- Penn State University biography.

- Meeting Mao Zedong on January 1, 1976 photo

- Aronson, Billy (2007). Presidents and Their Times: Richard M. Nixon. Cavendish Square Publishing. ISBN 978-0761424284.

- Marton, Kati (2002). Hidden Power: Presidential Marriages That Shaped Our History. Anchor. ISBN 978-0385721882.

- Eisenhower, David (2011). Going Home To Glory: A Memoir of Life with Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1961-1969. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1439190913.

- Frank, Jeffrey (2013). Ike and Dick: Portrait of a Strange Political Marriage. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1416587217.

- Gibbs, Nancy; Michael Duffy (2012). The Presidents Club: Inside the World's Most Exclusive Fraternity. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1439127704.

External links

[edit]- 1948 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American women writers

- 21st-century American women writers

- American debutantes

- Brown University alumni

- Chapin School (Manhattan) alumni

- Children of presidents of the United States

- Children of vice presidents of the United States

- Debutantes of the International Debutante Ball

- Eisenhower family

- Finch College alumni

- New York University alumni

- Nixon family

- People from Atlantic Beach, Florida

- Sidwell Friends School alumni

- Smith College alumni

- Washington, D.C., Republicans

- Writers from Chester County, Pennsylvania

- Writers from Washington, D.C.